What Is a Normal ECG in Athletes?

Up to 60% of athletes show ECG changes, and some of these changes are often striking to look at. The Seattle ECG criteria is often used to separate the normal from the abnormal ECG in an athlete. This is important, as many normal athletes undergo cardiac angiography and even pacemaker surgery because of misinterpretation of their ECGs.

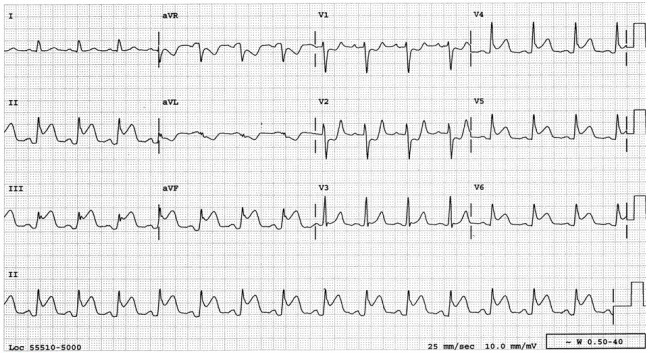

- Bradycardia: A low heart rate in an athlete should be self-evident—but it is not in the real world. Common normal athletic ECG patterns include: the inverted P-wave and junctional rhythm, Mobitz type I Wenckebach block, and sinus arrhythmia.

- Incomplete right bundle branch block (IRBBB): While only 10% of the general population has IRBBB, up to 40% of athletes have it as a normal pattern. This might be due to remodeling of the athletic right ventricle.

- Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH): It is normal for athletes to have voltage criteria for LVH. Of course, it is abnormal when voltage criteria comes with other LVH related patterns, such as left atrial abnormality, ST-segment strain patterns, left axis deviation, etc.

- Early repolarization: It is common and normal for athletes to have early repolarization, including terminal QRS notching. The pattern is especially common in black athletes.

- T-wave changes: T-wave inversions can be normal, or they can be abnormal. Up to one in three black athletes have terminal T-wave inversions in leads V1–V4. T-wave inversion patterns which can be mistaken for anterior-wall ischemia. Paying attention to the location of the inversions, however, is important. Namely, it is normal to have T-wave inversions in leads V1–V4 but not in V5 or V6 and not with accompanying QRS abnormalities or frequent premature ventricular contractions (PVCs).

- Notable abnormal findings in athletes: Some of the abnormal ECG findings may include any complete left bundle branch block, intraventricular conduction delay (IVCD) greater than 140 ms, left atrial abnormality, right ventricular hypertrophy, Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, QT prolongation (greater than 470 ms in males and 480 ms in females), high-degree AV block, atrial fibrillation/flutter, and high-density PVCs. Isolated (low-density) PVCs are considered benign.