Heart Failure

WHAT IS IT?

Heart failure does not mean that your heart has stopped working. Heart failure refers to a large number of conditions which affect the structure or function of the heart, making it harder and harder for the heart to supply sufficient blood flow to meet the body’s needs. It occurs when one or more of the heart’s four chambers lose its ability to maintain proper blood flow. This can happen because the heart can’t fill well enough with blood or because the heart can’t contract strongly enough to propel the blood with enough force to maintain proper circulation. In some people, both filling and contraction problems can occur.

Basic Facts (see below for more information)

- In the United States, 5.7 million people have HF and it afflicts 10 in every 1,000 people over the age of 65.

- The three major contributors to heart failure: coronary artery disease, hypertension, and dilated cardiomyopathy. HF can also result from heart defects, arrhythmias, unhealthy lifestyles, and more.

- The most common signs of HF are shortness of breath, fatigue, and swelling in the feet, ankles, legs, and abdomen.

- Medication can help stem progression of HF and most patients take a combination of a diuretic, ACE inhibitor, and beta-blocker. Lifestyle changes are critical to slowing heart failure.

- Some patients may need cardiac resynchronization therapy, ICDs, pacemakers, or heart assist devices.

- Patients with end-stage heart failure require heart transplantation to survive.

Background

The problems associated with heart failure depend a lot on what part or parts of the heart are most affected. Because the left ventricle is responsible for pumping oxygen-rich blood throughout the body, it is, in many ways, the most important of the four heart chambers and critical for normal heart function. When the left ventricle cannot contract normally, as might occur after a heart attack,, not enough oxygenated blood is propelled into the circulation. This can cause fatigue, shortness of breath, and a buildup of fluid in the lungs. If the left ventricle stiffens and the chamber can’t relax normally, as might occur with longstanding poorly controlled hypertension, the heart cannot fill properly when resting between heart beats. This can cause fatigue, shortness of breath, and a buildup of fluid in the lungs. Indeed, problems with either left ventricular muscle contraction or relaxation or both can result in the exact same clinical presentation. Although failure of the right ventricle can occur on its own, the most common cause of right ventricular failure is failure of the left ventricle (as left ventricular failure causes increased fluid pressures in the lungs, which eventually begin to affect the right ventricle).

Changes to the heart’s structure and function may precede the development of symptoms by months or even years (as with chronic hypertension) or may lead to heart failure quickly (as after a large heart attack).

The illustration on the right summarizes the various symptoms people with heart failure may experience:

Blood and fluid can back up into the lungs because of failure of the left ventricle. This is called pulmonary edema and may cause coughing, breathlessness with activities, and/or breathlessness when lying down.

Fluid can build up in the feet, ankles, legs and elsewhere (edema) as a result of higher pressures in the lungs, especially when the right ventricle is affected.

Most heart failure patients experience shortness of breath and fatigue.

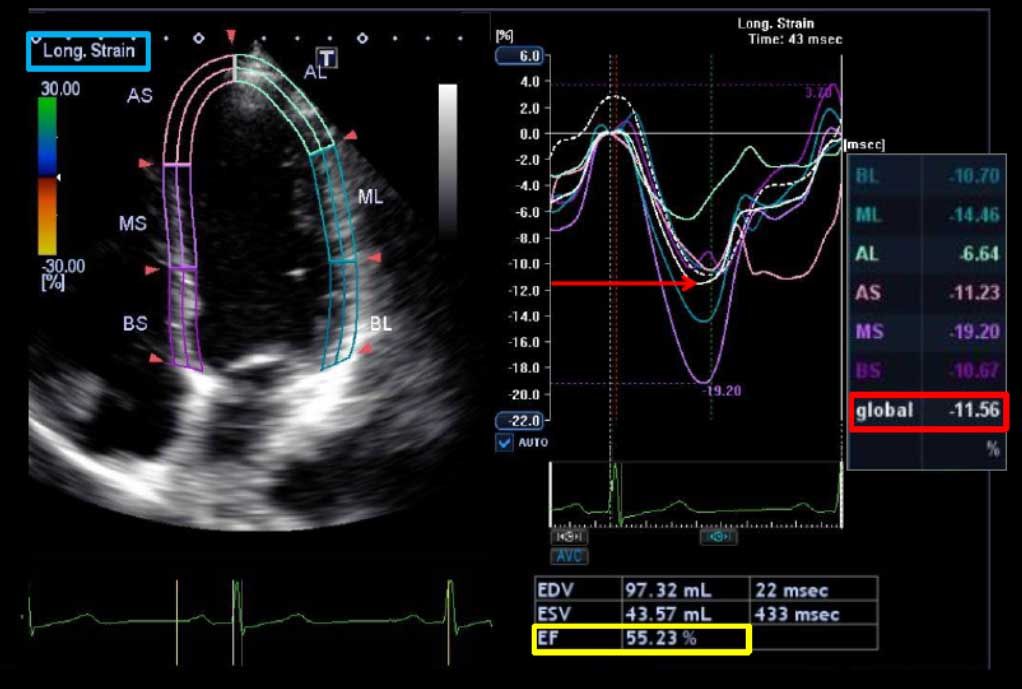

Most conditions which cause heart failure affect both sides of the heart to some degree and most frequently include some impairment of left ventricular function. One measurement that helps determine whether the left ventricle is working well is called the ejection fraction. This calculates the percentage of blood being pumped out of the ventricle with each heartbeat. Because not all blood is ever squeezed out, a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of about 50% to 70% is considered normal. (Right ventricular ejection fractions will be lower.) An LVEF between 35% and 40% indicates systolic heart failure; an LVEF below 35% increases the risk of deadly arrhythmias, making this degree of EF reduction especially worrisome.

Because heart failure worsens over time, it is considered a chronic condition and may be underway before there is any obvious indication that something is wrong. Initially, the heart tries to compensate for any loss of pumping action or capacity. It can do this in various ways: it enlarges, allowing it to stretch and contract more strongly to pump more blood; it develops more muscle mass to increase pumping strength; or it pumps faster to increase output.

Your body also attempts to aid the faltering heart in various ways. Blood vessels may narrow to increase blood pressure in an attempt to counteract the heart’s decreasing power. Or the body may redirect blood flow away from less important parts (top priority is always given to the heart and brain). Ultimately, however, these attempts to maintain normal function fail to compensate for the failing heart, leaving the individual chronically tired and perhaps experiencing breathing problems or other symptoms prompting medical evaluation.

Chronic stable heart failure can deteriorate due to any number of factors, such as an unrelated illness or heart attack. Known as acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF), it is the leading cause of hospitalization for patients over the age of 65 and is the most costly cardiovascular disease in Western countries. This is because ADHF is associated with a greater risk of death and complications. Once it has occurred, the risk of subsequent ADHF is high: about 1 in 5 will be rehospitalized within 30 days and half will be readmitted within six months.

There are various treatments for heart failure, and treatments will be more or less effective depending on the history and cause of the disease. When heart failure worsens and does not respond to any therapies (called end-stage heart failure), a heart transplant may be the only option for survival.

By the Numbers

Heart failure (HF) is a major and growing public health problem in the U.S. It is the primary reason for 12 to 15 million office visits and 6.5 million hospital days each year. Fully 75% of patients have hypertension before they develop heart failure. At 40 years of age, the lifetime risk of developing heart failure for both men and women is 1 in 5. The number of people experiencing heart failure has increased steadily during the last 2 decades; thanks to better treatment and improved survival rates, although this improvement has been less evident among women and elderly persons.

Heart failure is the most common hospital discharge diagnosis among individuals served by Medicare and more Medicare dollars are spent for the diagnosis and treatment of heart failure than for any other diagnosis. The increasing incidence of diabetes is having a huge impact on heart failure. In just 20 years, four times as many people diagnosed with heart failure have diabetes and the combination of these two diseases greatly increases risk of death. Fully 1 of every 8 death certificates issued in the United States mentions heart failure as a cause of death.

The more risk factors you have for heart disease, the greater your risk of eventually developing heart failure. If a parent has proven heart failure, the risk among offspring is greater (1.7-fold elevated risk) than someone without a parent who had heart failure.

Causes and Risk Factors

After age 65, 10 of every 1,000 people have heart failure. Many factors can lead to heart failure. Hypertension (high blood pressure) is a major contributor to numerous heart problems and conditions including heart failure: the lifetime risk of heart failure doubles in people whose blood pressure is greater than160 mmHg systolic /90 mmHg diastolic versus those whose blood pressure is less than 140/90 mm Hg.

Many of the behaviors that can lead to heart disease and heart attacks — such as poor diet, lack of physical activity, and substance abuse — also can cause heart failure. These lifestyle choices are linked to heart failure via the diseases that most often cause heart failure in the Western world: coronary artery disease, hypertension, and dilated cardiomyopathy. The latter is a disease of the heart muscle; any damage to the heart muscle, whether from previous heart attack, other diseases, a viral infection, or substance abuse, increases the chance of developing heart failure.

Heart valve problems, whether caused by disease, infection, or a defect present at birth, also can produce heart failure, as can irregular heartbeats (arrhythmias). Indeed, up to 40% of patients with heart failure experience a specific type of arrhythmia called atrial fibrillation and individuals with this combination of heart problems are at high risk for cardiac death.

Diabetes, especially because it increases one’s risk of developing hypertension and coronary artery disease, is another major contributor to the development of heart failure. In this case, gender makes a big difference in risk. According to the current American College of Cardiology (ACC) guidelines, diabetes only modestly increases the risk of heart failure for men, but it increases the relative risk of heart failure more than 3-fold among women.

Sleep apnea, which affects one’s breathing and reduces the amount of oxygen to the heart, does not necessarily cause heart failure but it can make it worse by increasing the heart’s workload.

Other factors also can injure heart muscle and subsequently lead to heart failure. These include treatments for cancer, such as radiation or chemotherapy; thyroid disorders; and HIV/AIDS. Good news: While heart failure may appear many years after cancer chemotherapy, it often improves greatly in response to appropriate therapy.

Beyond those contributing factors already mentioned, others that increase the risk for heart failure include:

- Age — People 65 years and older are at risk because aging can weaken heart muscle. Also, older individuals may have developed heart disease years earlier that subsequently led to heart failure. In this age group, heart failure is the number one reason for hospital visits.

- Ethnicity — African Americans are more likely than those of other races to have heart failure and they tend to suffer more severe forms, develop symptoms younger, get worse faster, go to the hospital more, and are more likely to die from heart disease than any other group.

- Obesity — The more overweight a person is, the more strain is put on the heart. Obesity also contributes to many other problems, such as diabetes and hypertension, that can cause heart failure.

- Gender — Men have heart failure at a higher rate than women, but more women end up with this condition because they tend to live to an older age when the disease is more common.

Signs and Symptoms

As mentioned above, the most common signs and symptoms of heart failure are

- shortness of breath or trouble breathing

- fatigue, tiredness

- swelling in the ankles, feet, legs, and abdomen; occasionally in neck veins.

Breathing problems can manifest in several ways. If you are out of breath just from walking stairs or doing simple activities, you have what doctors call “dyspnea”. If you wake up at night and are breathless, you have “paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea”. If breathlessness occurs when you’re lying flat, you may feel the need to sit up or be propped up with pillows. This inability to breathe easily unless sitting up straight or standing erect is called “orthopnea”.

It should be noted that some heart failure patients have exercise intolerance but little evidence of fluid retention, whereas others complain primarily of edema and report few symptoms of dyspnea or fatigue. When fluid build-up is present, there also may be weight gain, increased urination, and a cough that worsens at night and/or while lying down. Because not all patients have congestion in and around the lungs due to edema, the term “heart failure” is preferred today over the older term “congestive heart failure.”

Testing and Diagnosis

Heart failure is a complex clinical problem and no one test can confirm the diagnosis. First, a doctor or nurse will likely obtain a thorough patient history, including past and current use of alcohol, illicit drugs, standard or “alternative” drug therapies, and any history of radiation or chemotherapy. During a complete physical examination, your doctor will listen to your heart for telltale signs that suggest heart function problems and will listen to your lungs looking for any abnormal sounds. The exam goes beyond the heart and lungs to look for signs of heart failure, such as swelling in your ankles, and there will be an assessment of your ability to perform everyday tasks.

If heart failure is suspected, various blood tests will be ordered, which may help confirm the diagnosis and reveal the presence of disorders or conditions that can lead to or exacerbate heart failure. For example, thyroid-function tests can reveal overactivity (hyperthyroidism) and underactivity (hypothyroidism) of the thyroid gland, both of which can be a primary or contributory cause of heart failure. Another blood test will evaluate levels of a marker known as brain natriuretic peptide (BNP); increased levels of BNP have been associated with abnormal heart function, helping confirm the presence of heart failure in patients whose main complaint is breathlessness. BNP is also elevated during a heart attack, and in other settings, so your doctor will need to weigh the BNP result relative to your overall health status.

A chest x-ray may be taken as well an electrocardiogram (ECG), which measures your heart’s electrical activity. An echocardiogram (commonly called an echo), may be performed to measure your heart’s structure and function. This ultrasound examination (performed much like a baby ultrasound in pregnant patients) provides exquisite detail of the heart and how well it is working. The speed and direction of blood flow can also be assessed, providing an evaluation of heart valve function. The echo is also helpful in diagnosing right-side heart failure and measuring pressures in the lungs. Your doctor also may order an exercise stress test to see how your heart responds to an increased workload.

Another type of test is called radionuclide ventriculography, can be performed to assess LVEF. This test uses a small dose of an injected radioactive material to follow blood flow through the heart chambers. Finally, if necessary, coronary angiography may be performed. In this test, a small tube (catheter) is inserted into a blood vessel in your arm or groin area, threaded through the body’s vasculature to your heart where a dye is released. X-ray imaging helps reveal if any your heart arteries are blocked. Coronary angiography would be considered in someone who has clear risk factors for coronary artery disease, especially if other tests are suggestive of a prior heart attack.

Once diagnosed, heart failure often is categorized using the New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Classification system, which is based on symptoms and limitations to physical activity. NYHA stage I refers to patients who have no symptoms; NYHA stage IV refers to patients who have symptoms at rest. Stages II and III refer to situations where patients experience symptoms with progressively less exertion.

Guidelines issued by the ACC and American Heart Association (AHA) (presented in the summary slide) concentrate more on progressive stages of heart damage, beginning with a detectable insult or injury to the heart and key advances in staging based on structural changes and asymptomatic or symptomatic phases.

Important: Once heart failure has been diagnosed, at each visit your healthcare provider should measure your body weight as well as sitting and standing blood pressure. You’ll also be examined for fluid build up (in your arms and legs, for example). This is very important: you’re being assessed for what’s called “volume status” or level of fluid retention, which can influence drug therapy and suggest whether you are doing fine or perhaps getting slowly worse. With heart failure, it is critically important to detect sometimes subtle changes and intervene early (by altering medication, for example) rather than wait for the development of critical problems such as acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF). This emergency situation causes serious trouble breathing and can occur when fluid management and restriction does not work. ADHF requires emergency treatment including hospitalization, and puts additional strain on an already overworked heart.

Treatment

Heart failure itself is not a reversible disease, but there are many treatments that can reverse underlying causes and improve symptoms. Many of the drugs target changes in the body’s hormone status. Some hormones are naturally released by the body in response to heart failure but they can paradoxically either directly or indirectly damage the heart itself. Treatment goals for all stages of heart failure are geared toward keeping the disease from worsening and increasing both the length and the quality of life.

Lifestyle Changes

One reason for a thorough history and physical examination is to identify behaviors that might cause heart failure or accelerate its progression. Therefore, first and foremost, an individual with heart failure should focus on lifestyle changes. Controlling high blood pressure and weight are critical to improving the disease; both require a heart-healthy diet and increased physical activity/exercise. Your diet should be low in sodium, which not only helps with blood pressure levels but can also help reduce swelling (edema) in your legs, feet, and abdomen.

Recommendations regarding increasing activity and exercise have changed dramatically over the years. A hallmark of heart failure is a reduced ability to perform aerobic exercise, such as walking, swimming, or riding a bicycle. For generations, the management of heart failure included sharp restrictions of physical activity and exercise. Then, during the 1990s, 15 controlled trials of exercise training in heart failure demonstrated significant improvements in the amount of exercise that could be performed. Another 10 trials, during roughly the same period, reported other important improvements when heart failure patients exercised, including quality-of-life measures. As for the risks of activity, studies consistently showed a very low rate of adverse events during either supervised or home-based exercise programs.

Subsequently, the ACC and AHA guidelines formally recognized exercise training for patients with current or prior symptoms of heart failure. The guidelines state that exercise training leads to improvements “comparable” to that achieved with drug therapy and is in addition to the benefits of drug therapy. There is even evidence today that patients with heart failure benefit from cardiac rehabilitation programs, which had previously been recommended primarily for patients who had experienced a heart attack or undergone heart surgery.

Is exercise worth the time and effort? A recent large-scale trial, called HF-ACTION, placed half of the trial patients, all of whom had mild to severe heart failure symptoms (NYHA class II to IV), into an aerobic exercise program versus the other half, who simply had usual care. Those that exercised improved the amount of activity they could perform — enhancing the ability to perform day-to-day activities — plus they reported an improved sense of well being. Importantly, exercise was deemed safe in this group of fairly sick patients. There was almost what could be called a “dose-response” effect, meaning that the more exercise a patient achieved the greater the benefits.

Your doctor can discuss types of activities you can undertake, ranging from walking to bicycling, swimming, or low-impact aerobics; all of which provide excellent benefits and can be accomplished without straining your budget.

If you smoke or use illicit drugs, you should stop, and you should moderate your alcohol consumption per your doctor’s recommendations. You will hear these recommendations almost universally if you have heart disease — appropriate lifestyle choices truly are the foundation of good overall health and they can be especially critical in terms of managing heart failure.

Medications

There are various treatments for heart failure, most of which are geared towards treating specific underlying conditions. However, you should always tell your doctor about any and all medications, vitamin supplements, or “alternative” therapies you may be taking, including over-the-counter drugs. Some drugs can exacerbate heart failure and there are many potentially dangerous drug-drug interactions. This includes medications you take temporarily; for example, some cough and cold treatments may increase blood pressure while some anti-inflammatory agents (such as ibuprofen) may cause sodium retention and negatively affect kidney function. Even some herbal products may have unintended consequences in patients with heart failure, so remember that something seemingly innocuous or helpful may really be quite harmful in someone with heart failure.

Guidelines written to guide medical therapy recommend different treatments for those who are at risk of developing heart failure versus those at different stages of the disease. Different agents — even those in the same class of drugs — can be more effective or less effective at different stages. In brief, specific drugs are used to target particular problems, which is why your doctor needs to determine to the fullest extent possible how your heart failure started (or could start) and what structures or conditions are actually involved.

Most of the drugs used to treat heart failure target the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). This is a hormone system that regulates blood pressure and water (fluid) balance in the body. The drugs that target the RAAS are the principle means of controlling high blood pressure (hypertension), heart failure, kidney failure, and the harmful effects of diabetes.

Typical heart failure medications include

- Diuretics — Also known as water pills, these drugs help reduce fluid build up in the body. They lessen congestion in the lungs and help diminish swelling in the abdomen, legs, and feet.

- ACE inhibitors — Known as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, these drugs target the RAAS by reducing the formation of angiotensin, a substance that causes blood vessels to constrict resulting in increased blood pressure. ACE inhibitors lower blood pressure and reduce strain on the heart. Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) — Working at a different place in the angiotensin pathway, these agents block the action of angiotensin so that it has no or limited deleterious effect on the blood vessels and thus the heart.

- Beta-blockers — These drugs slow your heart rate and help lower blood pressure. This helps counteract the heart’s tendency to compensate for heart muscle weakness by pumping faster.

- Vasodilators — This class of drugs helps the blood vessel walls to widen or relax (called vasodilation), which helps normalize blood flow and reduce strain on the heart.

- Aldosterone antagonists — Again, the target is the RAAS. By helping the body get rid of salt and fluid, these drugs reduce the actual volume of blood the heart must pump.

- Digitalis — This specific drug helps the heart beat more strongly by increasing the force of the heart’s contractions. It has a mild effect on stabilizing some heart rhythm abnormalities as well.

Successful treatment of hypertension often requires at least two different types of drugs to control blood pressure. In the case of heart failure, blood pressure is only one of the targets of therapy. Consequently, heart failure patients will be routinely managed with a combination of a diuretic, an ACE inhibitor, and a beta-blocker. (Sometimes patients don’t tolerate ACE inhibitor therapy; these people often receive an ARB instead.) There is strong and compelling evidence that drugs are best used in combination for managing heart failure, so most patients with heart failure will end up taking at least 3 separate medications. Guidelines also recommend including digoxin, if necessary, as a fourth agent to help reduce symptoms, increase exercise tolerance, control heart rhythms, and help prevent hospitalization.

Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction

While low ejection fraction (EF) is typically used as a chief indicator of heart failure, approximately 15 to 20 million heart failure patients worldwide (one-third to one-half of heart failure patients) have relatively normal heart muscle contraction or preserved EF (40% or higher.) This is the predominant form of heart failure in elderly patients, particularly elderly women, most of whom have hypertension, diabetes, or both. Often these patients also have other heart issues including coronary artery disease or atrial fibrillation. Despite their preserved EF, they still have many of the typical symptoms and signs of heart failure, including shortness of breath, fluid buildup, and reduced quality of life. The main issue in many of these patients appears to be abnormal heart muscle relaxation. Individuals with preserved EF do have a better life expectancy than those with a low EF, but they still are at significant risk for dying and for requiring hospitalization at some point during the course of their illness.

Clinical trials are currently assessing how heart failure therapy might be different for individuals with preserved LVEF. Right now, guidelines for doctors suggest basing therapy on the control of factors like blood pressure, heart rate, and on addressing any health issues which may contribute to this form of heart failure (such as coronary artery disease, severe heart valve abnormalities, sleep apnea, and heart rhythm disorders). Many of the same medications which are used to treat patients with low EF are also used to treat heart failure patients whose EF is preserved.

Research eventually may suggest that individuals with preserved EF may do better on some drugs and not as well as others compared to heart failure with reduced LVEF. For example, a few recent studies have shown that ARB-type medications have not been very effective in improving survival or lowering hospitalization rates in patients with preserved EF-type heart failure. So it is possible that this class of drugs may not be as helpful for heart failure patients with normal ejection fractions as it is for those with reduced EFs. Much more research needs to be done in this area before firm conclusions can be made, however.

Two important points

First: Heart failure in elderly patients may be inadequately recognized and treated because both patients and physicians frequently attribute the symptoms of heart failure to aging. Furthermore, because the elderly are most likely to have heart failure with preserved EF, this condition may be missed with routine testing unless doctors are attuned to the possibility of this scenario. . If you have symptoms of heart failure (trouble breathing or inability to perform normal tasks of everyday living), and you are told that you don’t have heart failure, you might want to ask your doctor if you could have heart failure with preserved EF.

Second: No matter the kind of heart failure, there are no hard and fast rules about how an individual is affected by the disease. Patients with a very low EF may have no symptoms or physical limitations, whereas patients with preserved LVEF may have severe disability. Likewise, it’s hard to predict how someone will respond to therapy. Although medications may produce rapid changes in important markers of heart failure, signs and symptoms of the disease may improve slowly over weeks or months or not at all. That’s why an all-encompassing approach is important and includes recommended drug therapy, good compliance with prescribed medications, lifestyle changes, and attention to details such as weight gain or peripheral edema that might indicate disease progression. Your doctor can help a lot by getting you on appropriate drug therapy but your contribution with all the other aspects of the disease is important, too.

Acute decompensated heart failure

Fluid retention is the primary cause of hospitalization among ADHF patients older than age 65, with more than 1 million hospitalizations reported each year. Current treatments for ADHF have significant safety concerns and often are inadequate in managing fluid retention, especially without affecting kidney function or mineral balance in the body.

One big problem with treating ADHF is a lack of clinical trial data on which to base treatment decisions. Available guidelines suggest that reducing congestion is the primary objective, usually through salt and water restriction and diuretic therapy. However, there is not enough data to know whether this therapy, does much to change outcomes like rehospitalization and mortality. . A large registry of ADHF patients, called ADHERE, is collecting information about ADHF patients to help define successful treatment strategies for this critical disease.

Treating the whole patient

People with heart failure often have other health problems, too. Some drugs that might be quite effective as therapy for one condition might be problematic when given to individuals with another disease. Your particular treatment regimen may therefore vary from the regimens of other patients, depending upon your overall health situation. Nevertheless, it’s always wise to periodically go over your prescriptions with your health care provider, to make sure you understand the rationale for each medication and to know that no potentially beneficial medications are missing from your regimen.

On the flip side, some drugs used to treat other disorders actually have some benefit in heart failure patients. For example, metformin, which is the most widely prescribed drug in the U.S. for type II diabetes, has been shown to actually have specific beneficial effects on heart failure when given as diabetes therapy. Metformin was safe, even in patients with advanced heart failure, although the drug should be avoided in patients with severe kidney disease. Metformin should also not be used in patients without diabetes.

Surgery and Mechanical Assistance

To help deal with some of the underlying causes of heart failure, surgery may be one option to get the heart back into shape. For instance, if heart failure stems from a valve problem, valve repair or replacement surgery may be very beneficial. If coronary artery disease has blocked multiple arteries, coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery may be necessary. If artery blockage can be handled via angioplasty or stent implantation, the result may include a lessening of heart failure symptoms.

Another therapy used for heart failure is enhanced external counterpulsation (EECP), which uses three sets of inflating pneumatic cuffs attached to the patient’s legs that rapidly inflate and deflate. (They look like over-sized blood pressure cuffs.) The cuffs are applied to the calves, lower thigh, and upper thigh; then, they are inflated and deflated sequentially and timed to your heartbeat. A typical EECP treatment regimen consists of 1-hour sessions for 35 days. EECP improves blood pressure and blood flow, and in trials with heart failure patients, it improves exercise capacity and duration, NYHA class, and quality of life.

Despite optimal medical therapy and lifestyle changes, there may come a time when these interventions no longer control heart failure symptoms. This often occurs to individuals in NYHA class III or IV heart failure. In these cases, doctors may rely on mechanical means to help keep the heart beating in as strong a rhythm as possible. Some options include:

- Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) — When the left and right sides of the heart no longer work together, the heart becomes less efficient in its ability to pump blood through the body. CRT “resynchronizes” the two sides to work in sequence and improve pumping function. CRT involves implanting a pacemaker-type device with electrical leads to specific areas of the heart, such as the left ventricle. The CRT device stimulates the left and right ventricles to help restore a coordinated, synchronous pattern to the heart’s pumping action. This is also referred to as bi-ventricular pacing.

- Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) — For heart failure patients with recurrent, rapid, irregular heart rhythms who are at risk of sudden cardiac arrest, ICDs can check the actual speed and rhythm of the heart and shock it appropriately to return it to normal rhythm. Some ICD devices have pacing capability, too. These combination devices can convert some sustained arrhythmias to normal rhythm without the need of an electrical shock to the heart.

- Left ventricular assist device (LVAD) — This surgically implanted device helps a weakened heart pump blood. Used primarily in very sick patients, it is often considered a bridge to heart transplantation.

- One other device still being evaluated is a mesh-like device that wraps around the heart to reduce heart dilation and heart muscle stress. In a small study called ACORN, the device improved LVEF, stopped or reduced heart chamber dilation, improved NYHA class, and was associated with other benefits in heart failure patients who had it implanted. This approach remains experimental.

Heart Transplantation

When medical and surgical treatments cease to be effective, a patient is said to have reached end-stage heart failure and may be a candidate for heart transplantation. A patient will have to be matched to a donor — that is, a person whose tissue is as similar as possible to the recipient — to reduce the risk of the body’s rejecting the donor heart. There is a balancing act required when choosing heart transplant candidates; the patient must be sick enough require a donor heart but healthy enough to survive the surgery and gain long-term benefit from the new heart.

According to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, survival rates for heart transplant patients have improved over the past decade or so. About 88% survive the first year following the surgery, 72% survive for 5 years, 50% for 10 years, and 16% for 20 years. However, given the limited availability of donor hearts, only about 2,000 heart transplants are performed annually in the U.S.

In transplant surgery, a patient is attached to a heart-lung machine, and the entire diseased heart is removed from the body and replaced with the donor heart. About 90% of heart transplant patients return to normal activities of daily living, although fewer than half return to work due to a variety of reasons.

Living With Heart Failure

Because there really isn’t a cure for heart failure, your best course of action is to stay as healthy as possible for as long as possible by following the advice and treatment plan provided by your doctor. Start by sticking with your medication schedule. If you experience side effects, talk to your doctor quickly. Don’t stop a medication until your doctor says it’s OK; some drugs need to be halted over time and stopping them immediately may be dangerous. Also, let your doctor know if you have missed medication doses, failed to refill a prescription, or are having difficulties with the costs of your regimen. Heart failure treatment is truly a partnership between the patient and the health care provider, and success is greatest when communication is open and forthright. Treatment adjustments are based upon your response to therapy – if your doctor does not have the complete picture of what you are really doing, those treatment adjustments may end up being counter-productive, or even dangerous. Also, always tell your cardiologist if you are prescribed any new medications by other doctors to avoid drug-drug interactions.

Be aware that respiratory infections, such as flu and pneumonia, can be very worrisome if you have heart failure. People with heart failure have a much greater risk of serious complications if they get the flu. Vaccines usually protect people from the flu, but the body’s immune response appears to be poorer in people with heart failure compared to healthy individuals. It is still very important that heart failure patients get a flu vaccination, but additional preventative steps might be needed to reduce exposure to the flu virus in patients with heart failure. During flu season, this might include reducing exposure to crowds of people, more frequent hand washing, and reduced exposure to individuals known to have the flu.

Also, make all necessary lifestyle changes to get and stay as healthy as possible. Many of us prefer to relax rather than to be active, and apple pie rather than an apple, but when your life is on the line in terms of both its quality and quantity, then carrots and celery may look more appealing and a nightcap less so. Make your diet as healthy as possible and get as physically active as your doctor advises. And consistency is important; it’s not just a week’s worth of commitment but rather a long-term objective that enhances life and improves quality-of-life after a diagnosis of heart failure.

Understand that this disease requires a great deal of attention and coping, especially if symptoms worsen. The nature of the disease may cause depression in some people. It is natural and most certainly NOT a personal failure. Make your doctor aware of how you are feeling mentally as well as physically so that you receive further treatment or support as needed. And realize your family may need support, too, in helping you deal with heart failure. It can be a challenge but for those who take on the challenges, the reward can be a longer and better life.

Prevention

The best way to prevent heart failure is to live a healthy lifestyle. It’s a common theme that needs regular repeating since so many health problems are in essence self-inflicted through poor diet, lack of physical activity, smoking, and other lifestyle choices. More than 50% of the deaths and disability from heart disease and strokes could be cut by a combination of simple, cost-effective actions to reduce major risk factors such as high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity and smoking. How successful are these preventive measures: Optimal blood pressure control alone, for example, decreases the risk of new heart failure by approximately 50%.

Because heart failure often develops from other cardiovascular diseases, preventing those diseases in the first place will help prevent heart failure. Yet, there is no magic key to preventing heart failure. If you have no risk factors that predispose you to the disease, then keeping healthy overall should keep your heart that way. If you are at a higher than normal risk of heart failure, preventive measures mentioned here can greatly reduce your risk. Remember: big benefits come from simple changes to diet, activity, and overall lifestyle.

**Source: Cardiosource- American College of Cardiology.